Part of our Emotions and Ethics series, today’s blog on using historical photographs is written by Michaela Clark and includes the video of her presentation at the ‘Emotions and Ethics: the use and abuse of historical images’ webinar. The paper was titled: ‘Trace, Tissue, Touch: what it means to look at historical clinical photographs.’ Michaela is a PhD candidate at the University of Manchester’s Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine (CHSTM). Her ongoing research focuses on the history of medicine and the politics of (scientific) representation with a particular emphasis on 20th century clinical photography in South Africa.

Why We Should Think About Touch – Using Historical Photographs

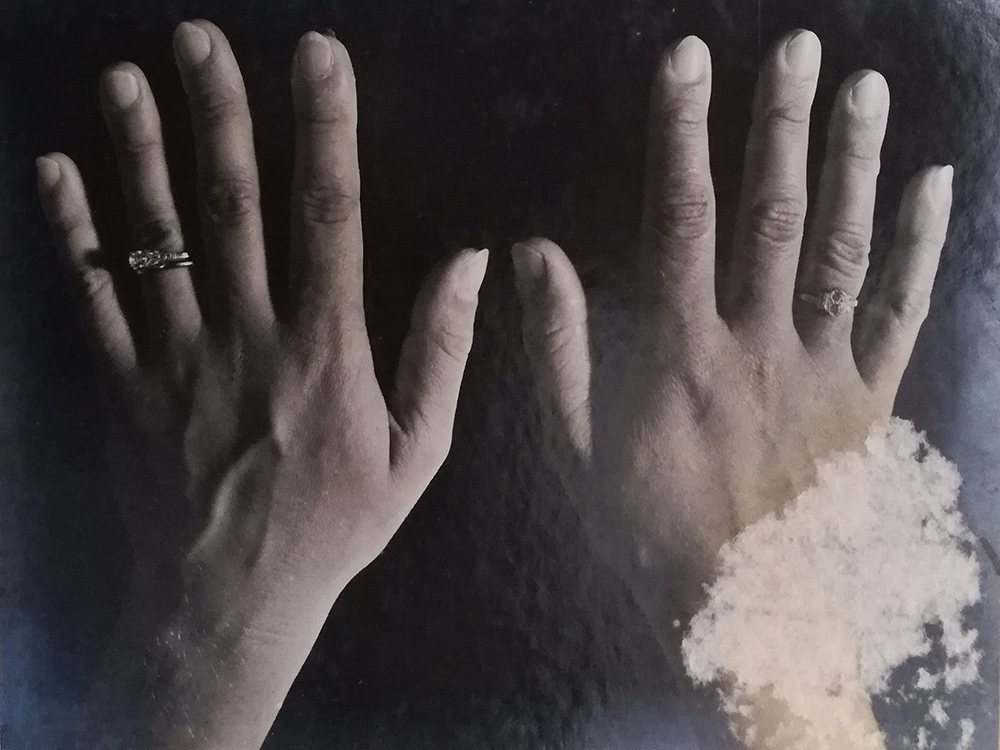

The notion that photography is a ‘tactile’ medium might come as a foreign concept to those used to encountering images of this kind in digital form. Seen on screen (that of the digital camera, the mobile phone, or the computer), photographs can easily appear as mere visual data: they offer a replica of the real world in the form of an image. However, when these representations are made through the use of an analogue camera or processed and printed within a darkroom, their essential makeup seems to change. Embedded in glossy or matt paper, these images become objects – things to be handled, passed from person to person, their surfaces open to the lightest touch of a finger or the damaging heat of a match.(1) Photographs can be loved and cared for or despised and harmed; but both their safekeeping and their destruction suggest something about our perception of these visual and material artefacts.

How we treat a photograph is namely often in relation to the way we relate to those depicted therein. Be it a long-lost ancestor, a loved family pet, or even a younger version of ourselves, we feel strongly about these images because they are more than just resemblances or visual information – they hold something of those they represent within their frame. Throwing away a photograph of one’s mother may feel like having done her wrong; cutting or scratching out the photographed face of a scorned lover may offer cathartic release; while hurling darts at a poster of a disgraced politician can offer comic relief. These attachments (both of a positive and a negative kind) suggest a relationship between us and the medium of photography that is difficult to pinpoint – something intimately felt and yet hard to articulate.

Rather than simply an object to be handled, tactility (the capability to be touched) is arguably part of the very make-up and function of the photographic image. Without the touch of light, the material world in front of the camera would never be captured by the lens or imprinted onto photographic film. Within the darkroom, this tactile encounter continues as, depending on the printing process, a negative image might even ‘kiss’ the emulsion of another page in order to produce the final (positive) representation.(2) Indeed, even the contents of a photograph can ‘touch’ or ‘pierce’ the viewer on an emotional level, in the sense that Roland Barthes famously highlights in Camera Lucida (1980).(3) In these examples, it is both the physical making and make-up of the photograph as well as the sense that we ‘encounter’ those we see within its image that makes the medium tactile.

Image courtesy of the Pathology Learning Centre, University of Cape Town

With my ten minute presentation at the 2020 AboutFace workshop, I propose that it is tactility which offers an avenue for thinking through the intimacies of old photographs – even those of a clinical kind. Rather than mere medical data and copyrighted pictures, historical clinical photographs are notably highly complex and layered entities; they are remnants of lives lived and experiences had. Sometimes, these records can offer glimpses of an institutional past now forgotten, or provide evidence of a medical ‘way of seeing’; but images of a clinical kind also provide a visual trace of the individuals they depict. By unravelling the tactile and emotive dimensions of the photographic medium and its clinical output in terms of re-presentation, it is my hope to rethink contemporary attitudes towards regulating material of this kind.

References:

(1) Elizabeth Edwards as well as Geoffrey Batchen independently do a wonderful job of articulating the tactility of historical photographs. In particular, see “Photographs and History: Emotion and Materiality” by Edwards (2010) as well as “Ere the Substance Fade: Photography and hair jewellery” (2004) by Batchen.

(2) This method is known as contact printing. See this demonstration for an example of the method.

(3) Barthes calls this aspect of photography the punctum, and compares it to the visual content of the image which he calls the studium.

Professional Profile: https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/michaela.clark-postgrad.html

Twitter Handle: @Michaelaclarkba