Visual representation is key to many themes of AboutFace. Our work on face transplantation necessarily exposes us to medical images of faces, in various states of injury and in different environments. Some of these images have also been made public, circulated by global media outlets. Such photographs of face transplant recipients often juxtapose a ‘before’ and ‘after,’ a comparison that implies a moment of transformation from ‘injured,’ to ‘fixed.’ This is not a new development. It dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, where imaging has allowed for the comparison and cataloguing of difference to enable practitioners to assess progress and outcomes. However, as Fay Bound Alberti recently explained in an article for The Lancet, for arts and humanities scholars, the use of medical imaging is more complex.

As a team, we are careful to honour and respect the boundaries of the patient and have taken the decision not to include patient images routinely on the website. But the same images that we choose not to use circulate widely on other forms of media, and people expect to see them. And we are not alone in grappling, as historians, in the ethical use of images.

On 17 June, we were joined online by a community of researchers for a workshop on ‘Emotions and Ethics: the use and abuse of historical images.’ This blog seeks to draw together some of the common threads of the webinar, and some of the tensions that arose from our discussion. We include the video of Fay Bound Alberti’s short introduction to the event, which explains why we, as a project, are so interested in images and their uses. This blog will also outline Ludmilla Jordanova’s reflections on the papers given during the webinar.

One of the core themes of the day was the responsibility that researchers have to our work and to the subjects of that research. There are political, ethical and emotional implications to what we do, and how we use images, which necessarily impact on our approaches, processes and outputs. This was evident throughout the webinar. Our speakers engage with their images in different ways, asking different questions, and coming to different conclusions on whether we should, or should not, show or publish historical images as part of our work. But how do we as researchers manage in a world where access to information and images is ever increasing? What underpins our motivations to protect or display images? And what does it mean to do so?

We are reminded that the historian cannot truly know the response a viewer will have to the image that they publish. Some viewers may react in vastly different ways to others, something that we notice in the classroom as often as we do in theatres, cinemas, and even in our own homes. This diversity in response complicates the question of whether we should protect images from viewers, or vice versa. It is worth considering the relationship that we have with our readers: do we owe them the opportunity to see the images that we are working with? We may underestimate the empathetic capacity of our readers, but could it be our duty as historians to offer readers the capacity to increase their empathetic experience with actors in the past?

The closing roundtable discussion touched on the reality that it is impossible to moderate or prevent inappropriate or macabre reactions, and we recognised that sensitive images will be circulated whether or not we approve of it. These discussions ran throughout our webinar, and it became clear that different opinions and approaches were present in the ‘room.’ Where it could be seen as moralistic, or controlling to hide the images we use from our audience, it was also strongly argued that the subjects of photographs have a right to confidentiality, to privacy. The ethical issues surrounding the use of images are certainly complex, and the webinar revealed tensions that are not easy to resolve. But this is part of debate, discussion, and progress. One of the key arguments made in Ludmilla Jordanova’s response is that all historical practice needs to have ethics at its heart.

As previously mentioned, AboutFace has adopted the position that we will limit the use of patient photos on our site, so these discussions raise further questions about our choice to do so. But what happens when we don’t show an image? What sensory and emotive capabilities are we drawing on in our readers and our students in these instances? These questions are posed with no easy or finite answers. Discussion on this subject prompted us to think about the contexts of the images that we work with, because each speaker referred to different kinds of images and used them in different ways. Context necessarily dictates how we approach, understand, and disseminate images, and we were encouraged to think about the photographers, artists, and documenters who created the images that we use. We feel a particular unease when seeing pictures of enslaved peoples, lynched bodies, and others who presumably did not consent to their image being taken, or later shared. To look at these images is seemingly to replicate the eye of the oppressor, or perpetrator. The imbalance of power in the image is palpable and uncomfortable. So context is a vital part of our consideration as a project of what we will, or will not show, but it seems that it may be down to each of us as individuals, or teams, to consider our own particular stance on different images, and types of images.

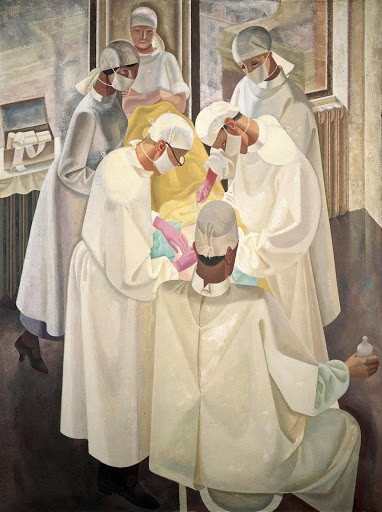

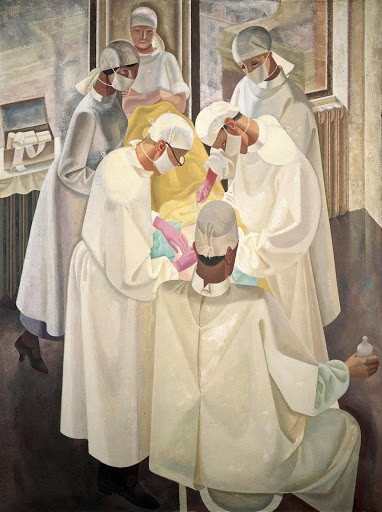

A surgical operation. Oil painting by Reginald Brill, 1934-1935. Credit_ Wellcome Collection. CC BY

But if we do hope to move towards a working ethical model for using and reproducing images, how might we do it? Collaboration with others is at the heart of academic practice, and is absolutely central to the work we do on AboutFace. We talked a lot in the webinar about the many benefits of interdisciplinary work, and how bringing together researchers from different fields will be vital to reaching any sort of consensus on the issues that were raised during the course of our webinar.

As a team, we are committed to being critical about the ways in which we use images on our website, in our publications, and on our public platforms, such as social media. As our website undergoes a redesign in the next month, we intend to build in the functionality to blur out sensitive images that we do choose to use. This way, with appropriate content warnings in place, our audiences can choose whether to click to ‘clear’ the image and view it, making a conscious decision of whether or not to do so. This does not mean that we will always show images, or host particular images on our website. We recognise our own role in making conscious decisions as to what we show, and do not show, based on the context of both image and platform, and in light of the discussions that began in the Emotions and Ethics webinar. Guest bloggers, including our webinar participants, will be given the choice themselves about what they want to include in their posts, and as a team we may choose to reflect with them on their decisions. This is, for us, very much an ongoing process.

It is perhaps no coincidence that this blog has posed more of the questions that arose out of our discussion than answers, and this is because we are only at the very beginning of our work on this. In the coming weeks, we will publish a number of blogs and some of the talks from the webinar, and will be asking further questions on our Twitter feed about the issues raised. We want you to contribute to the discussion. So get in touch! Tell us how you feel about the use of historical images. Do you have thoughts on any of the questions that we have raised here in this blog? We would be delighted to hear from you.