The fourth and final blog in our Halloween series, written by Paddy Adamson, brings together the key themes of Hollywood and disfigured faces. As a researcher in film, and a member of Face Equality International’s Lived Experience Group, Paddy brings a unique perspective to the topic. Don’t miss the rest of the series, starting with Fay Bound Alberti’s introduction, Sara Wasson’s blog on Les yeux sans visage and Lauren Stephenson’s analysis of The Eye. Let us know what you think!

Disfigured Faces, “Accursed Ugliness”, and Hollywood

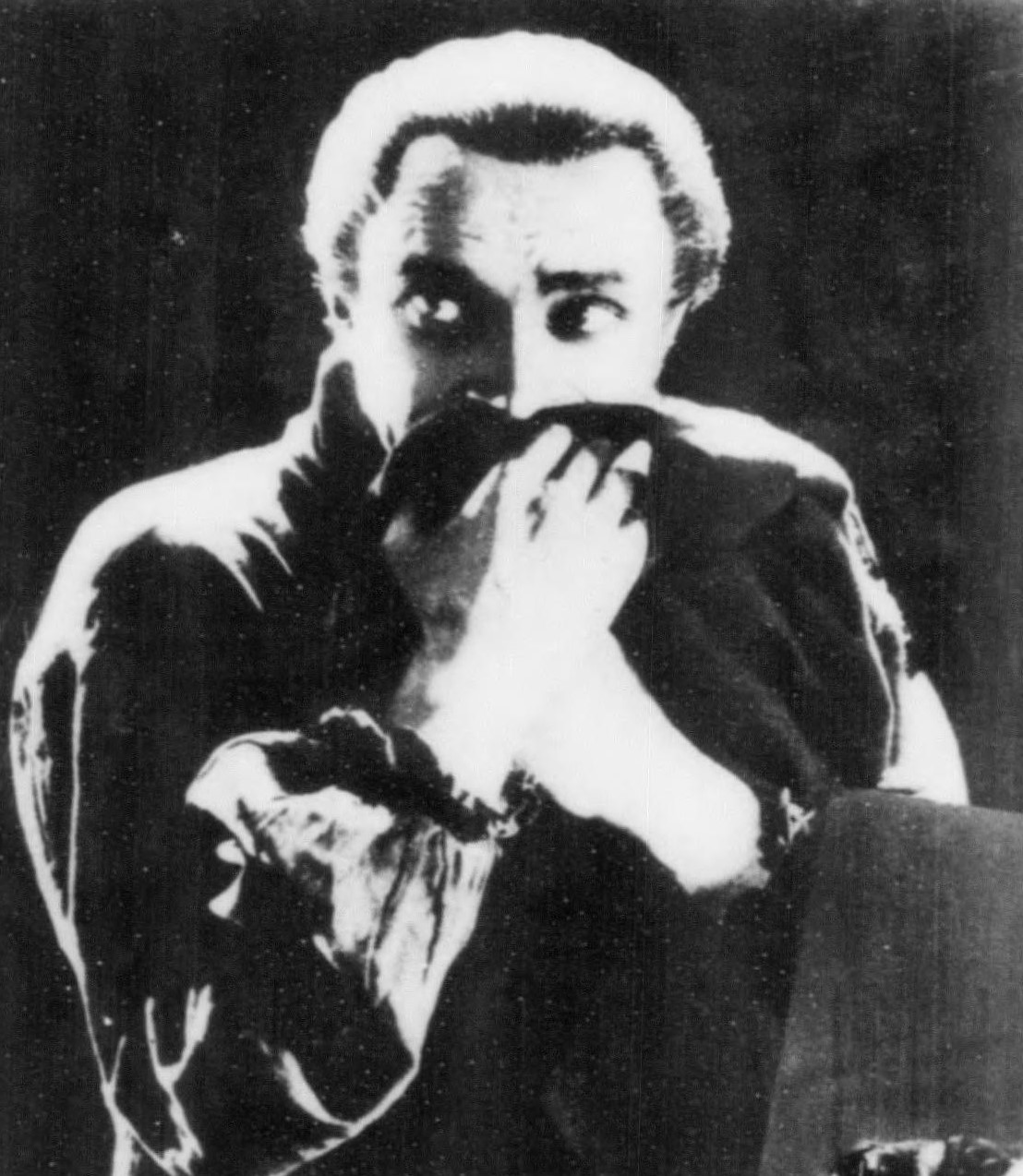

One of the best-known scenes in all of silent cinema unfolds about halfway through Rupert Julian’s The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Young soprano Christine Daaé (Mary Philbin) has been carried down into a suite prepared for her in the cellars under the Paris Opera House by the Phantom (Lon Chaney), a mysterious masked composer who haunts the venue. He promises her a great career, providing she can devote herself to following his orders.

But curiosity about what lies beneath her mentor’s disguise gets the better of her. Stealing up behind him as he plays “Don Juan Triumphant” at his organ, peering over his shoulder as he faces the camera, she snatches the Phantom’s mask away, revealing directly to the audience a cadaverous face of sunken cheeks, protruding teeth, and flared, elongated nostrils. When he turns to look at her, intrigue gives way to screams; the film cuts between the Phantom’s true face and the terror and disgust it inspires in hers.

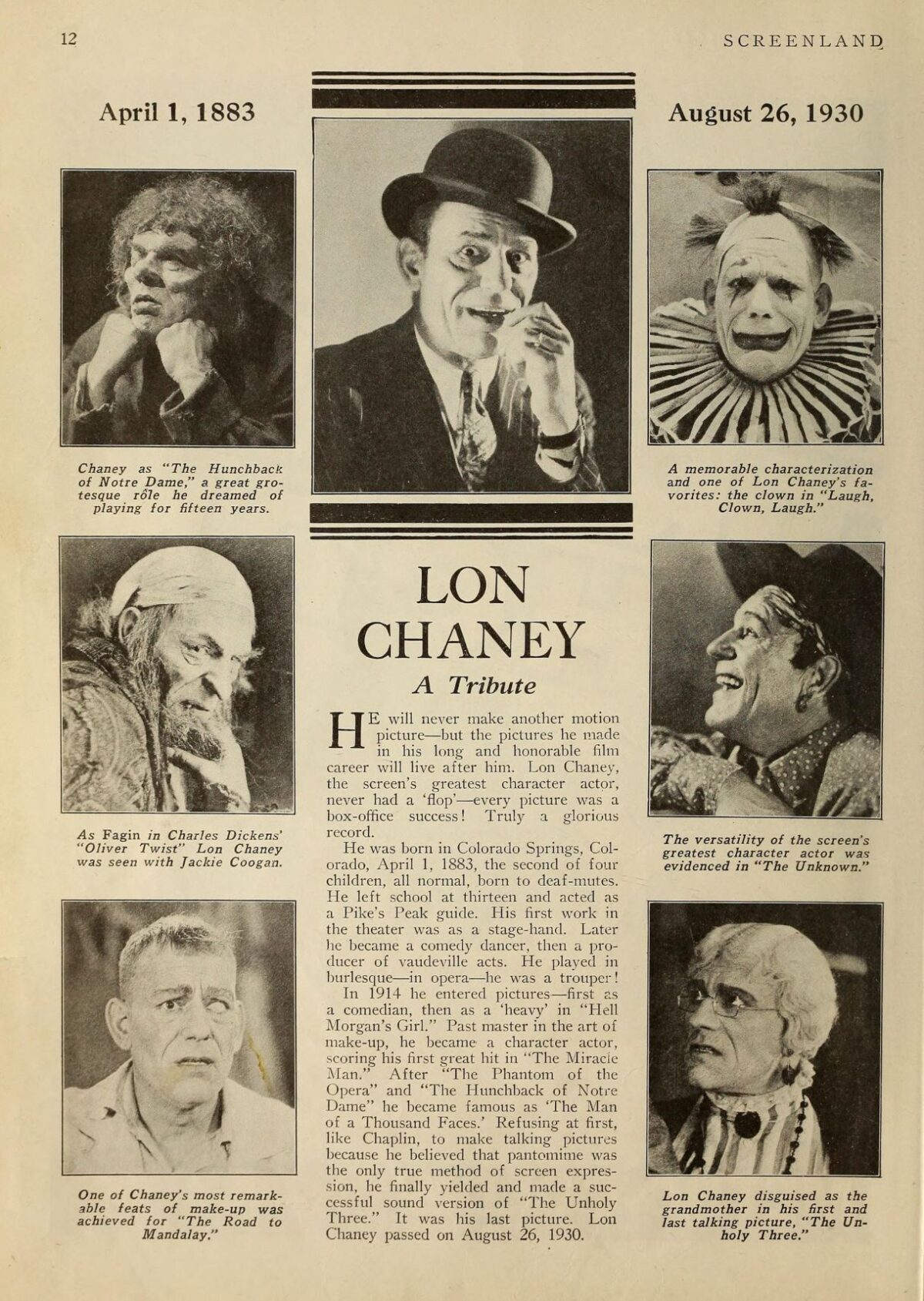

Said to have led to screaming and even fainting among moviegoers of the day, the Phantom’s unmasking is a shocking spectacle of physical difference and an iconic moment in horror film history – the unveiling of a face that has continued to fascinate in the near-century since. Created by Chaney himself, an actor famed for his extreme transformations, the villain’s look was kept secret until release. Today, his elaborate make-up can be imitated for the price of a high-end Halloween mask.

“Feast your eyes”

Yet, for all that the Phantom’s command as he forcibly turns the cowering Christine’s face toward his – “Feast your eyes – – glut your soul on my accursed ugliness!” – could equally be directed at the film’s audience. There is more to the scene than the thrill of seeing Chaney’s make-up artistry paraded on screen. It provides a revelation vital to the story. Confirmed by the disclosure of his deformed face is the Phantom’s monstrous true nature. The corrupted body of this gruesome physical spectacle befits the corrupted soul of this dangerously deranged outcast from Devil’s Island, his disfigurement the outward expression of the ugliness within.

Film still from The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

For me, as a disfigured viewer, this is the most striking aspect of this iconic moment. Not only is it testament to the longevity and pervasiveness of an all too familiar tendency, unavoidable at this time of year – the imitation of appearance-altering conditions in the name of a “spooky” costume – but it is an uncomfortable reminder of what it means, in the codified world of Hollywood cinema at least, to be facially different.

Physical Appearance as Cinematic Shorthand

Filmmakers have long exploited the meaning-making potential of distinctive physical characteristics, using non-normative appearances as an expedient shorthand for character. The most notorious example of this physiognomic logic is the prevalence of facial scarring among movie villains. Examples range from the monstrous of horror cinema – the burn-scarred Freddy Kreuger foremost among them – to the crime lords and Sith Lords of the latest James Bond and Star Wars blockbusters. Visible evidence of a past gone awry, stated or otherwise, their scars offer a convenient rationale for the malevolent course they now follow.

At the same time, there can be little doubt that the appeal of figures from the Phantom to Kreuger owes also to a fascination with such bodies and the uncomfortable feelings they are supposed to excite. They are the frightful icons behind many a Halloween costume, after all, evidence of a pleasure found in the display or performance of physical difference that can be traced back through the history of film and the freak show. Chaney made something of a career of it, earning the nickname “The Man of a Thousand Faces” for the lengths he went to: strapping his lower legs to his thighs to play a double amputee in The Penalty (1920); labouring under a skin-tight rubber suit and seventy-pound hump as Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923); and apparently combining his famed make-up skills with painful wire hooks to create his iconic Phantom.

Lon Chaney tribute (Screenland, November 1930)

The Man Who Laughs

Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs (1928) typifies this marriage of exploitation and empathy, using the non-normative appearance of its protagonist to directly interrogate conventional ideas about the face and the role it plays in how we understand ourselves and others. Originally planned as a Chaney vehicle, this adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel stars Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine, a travelling show attraction famous for his wide frozen grin, carved into his face as a child by a Comprachico surgeon under orders from the King of England.

While his condition does not, in theory, preclude his entry into the spaces and pursuits enjoyed by the masses, Gwynplaine’s world is circumscribed by his facial difference. Most welcome on society’s edges, in carnivals and freak shows where difference is a valued commodity, he internalises the daily ridicule and the aesthetic and moral judgements of a callous, grotesquely prejudiced, yet superficially “normal” public; he fears he is unworthy of the woman he loves, Dea (again played by Philbin), for her blindness prevents her perceiving the real him.

To portray a man who can only laugh, Veidt’s wide grin was held in place using a bespoke, and apparently painful, appliance that deprived him of access to normative facial expressions, along with the social cues associated with them. Where the face is conventionally seen as inseparable from selfhood, the foremost means by which we recognise each other, Gwynplaine’s face not only fails to reflect his inner self but seems to contradict it, thanks to the fixity of its lower half; when not covering his mouth via a protective gesture of sorts, he is seen to grin his way through incidents to which such a reaction rarely seems appropriate. His character divorced from his appearance to jarring ends, the result invites audiences to search for an understanding of his agony in his eyes and comportment, and, in the process, perhaps reflect on their assumptions about how a face should react and look.

The Man Who Laughs (from Der Kinemtaograph, Feb 1929, 3)

A Damaging Reliance on Disfigurement

And yet, for all the nuance, or at least ambivalence, that The Man Who Laughs brings to its handling of disfigurement – being, at once, indebted to and critical of the exploitation of facial difference – the film’s enduring place in the popular consciousness again owes overwhelmingly to the unusual look of its protagonist. In 1940, a photograph of Veidt in make-up as Gwynplaine was used by DC Comics artists as a model for a new villain: the Joker – flamboyant nemesis to the noble, honourable Batman.

A staple Halloween costume today, the Joker has gone through numerous incarnations in the intervening eight decades, with the extent and cause of his scarring and famous malevolent grin being repeatedly reimagined. The latest, in 2022’s The Batman, finds him with full-body scarring and a permanent smile attributed to a congenital condition. Director Matt Reeves explains, “…he’s had this very dark reaction to it, and he’s had to spend a life of people looking at him in a certain way…and this is his response.”

Nearly a century on from the unmasking of Chaney’s Phantom, and in a world where media images are routinely decried as a source of body dissatisfaction, Reeves’s comments illustrate the extent to which popular cinema’s damaging reliance on disfigurement as a visible expression of inner corruption or evil continues to go unexamined in many circles. Moreover, they speak to the unique challenges faced by the facial difference community and how these extend beyond the cosmetic and the medical, beyond even the more overt forms of discrimination and abuse to which many of us have grown up accustomed.

Everyday Prejudice

Yet, for all that characters with facial differences are disproportionately given (often lurid) backstories involving some kind of “dark reaction” to what is treated as an inevitable social stigma, the toll such everyday prejudice can have on the life experiences and mental health of those affected by it has rarely been addressed via bespoke legal protections or support. Recent years have, it should be highlighted, seen some more promising signs on this front: the British Film Institute’s 2018 commitment “to stop funding films in which negative characteristics are depicted through scars or facial difference”, and the ongoing efforts of Face Equality International, a global alliance of NGOs working around disfigurement, advocating the overdue recognition of facial difference as a human rights issue in its own right. These are significant steps and, in their being so, reminders of how much remains to be done.

Author Bio

Patrick Adamson is an editor and independent film researcher who lectured at the University of St Andrews from 2021 until 2022, having received his PhD from there in 2020. Specialising in silent Westerns, early popular historical filmmaking, and universalist discourses in 1920s Hollywood, he has been published in journals including Film History and received awards for his research from BAFTSS (British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies) and SERCIA (Société pour l’Enseignement et la Recherche du Cinéma Anglophone).

He is a member of the Face Equality International Lived Experience Working Group.