By Victoria Hoyle, Research Associate

AboutFace is an interdisciplinary project, which draws on research and practice across the humanities and sciences. But our subtitle identifies it as a history of face transplants; specifically, an affective and cultural history. This is not accidental: we are based in a History department and staffed by historians. A historical orientation has been critical to both the project’s design and its objectives from the start. Yet our contemporary-focused, qualitative methodology often doesn’t fit neatly into the category of what people imagine ‘history’ to be, even within the discipline itself. At the same time historical perspectives are generally unfamiliar to researchers and practitioners working on transplant in the social and life sciences. We have already encountered significant paradigmatic differences, which make it difficult to communicate our aims and methods outside of humanities spaces.

When I joined AboutFace in October I spent the first month not only explaining my new job, but also justifying its status as history and arguing for its value to clinicians and medical teams. It often seems like we belong everywhere and yet nowhere. Now in my third month with the project I continue to grapple with disciplinary questions:

- In what ways is AboutFace history?

- What does history bring to a study of face transplants?

- And what is the role of history more broadly in biomedical practice?

To some extent the answers are straightforward. One of our aims is to contextualize face transplants in the development of plastic, reconstructive and transplant surgeries since the Second World War. The divergence of reconstructive and cosmetic surgeries post-1950, and their respective social and cultural positioning, have impacted significantly on contemporary perspectives on facial difference and ‘disfigurement’, and thus on how face transplants are conceived. This history has received less concerted attention than the First World War and its immediate aftermath (see, for example, the 1914FACES2014 project) and is ripe for investigation. During the same time frame solid organ transplant (of heart, liver, kidneys and lung) have become routine, regarded through a lens of surgical progress and medical miracles. The early 21st century development of face transplants, which sits at an intersection of these specialisms, acts as an access point to critically reflect on these broader, longer narratives.

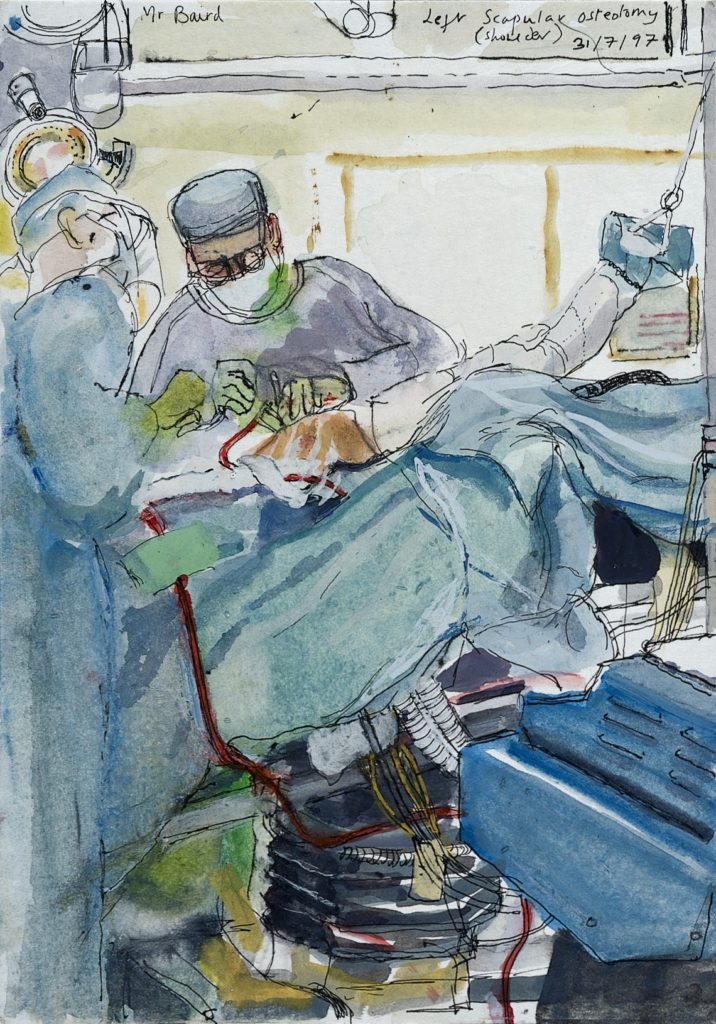

A better understanding of the past will help to problematize the status of face transplants as medical treatments, and to unpick both professional ethical concerns and the response of the popular media. When face transplants were first proposed they were imagined within a cosmetic frame, as a kind of cosmetic surgery ‘gone mad’. For example, in 2006 a Royal College of Surgeons’ report on the procedure speculated on the potential of transplantation as a treatment for aging. More recently they have been seen from a reconstructive perspective, as life-saving and necessary operations in the case of severe injuries (Warning: This link contains graphic images of a face transplant patient immediately post-surgery). Using archives and oral histories, we will produce historical accounts that explore how these changing discourses of medical innovation intersect with, and are influenced by, the past.

But the focus of AboutFace is not only on the ‘pastness’ of facial transplantation. It is very concerned with its ‘presentness’ and future. Whilst our line of sight stretches back to 1950, our starting point is the late 1990s and early 2000s when the surgery was first discussed as a realistic objective. The project’s primary subject will be the performance and practice of face transplants since 2005, and the social, cultural and emotional factors that have shaped their implementation around the world. Most of our source material will be qualitative data collected through focused ethnographic observation and semi-structured interviews. This approach prioritises the living voices of those involved in transplants – from recipients and their families to extended medical teams – and aims to generate an emotionally and historically informed framework for developing sustainable transplant practices. This makes sense when working with surgeons, extended medical teams and patients, whose orientation is towards their present and future experiences. Their priority is producing knowledge that is relevant and meaningful now, and which contributes towards improving the health and wellbeing of people with facial differences. This is a priority which I would say we share.

But these are methodologies that arise in the social sciences and produce very different types of ‘data’, which must be analysed and treated using techniques and practices that are less familiar to historians. The closest analogy is oral history practice, which produces a form of qualitative data which historians conceive as a primary source: the collection of living people’s memories and testimonies through interview and personal narrative. AboutFace is deeply concerned with individual experiences in ways that are not dissimilar, because this is a small, developing surgical field in which personality and memory have played (and will continue to play) a key role. Indeed, we will study discreet episodes of face transplant history using oral history methods, as for example in the case of ‘the transplant that never was’ at the Royal Free Hospital in London between 2003 and 2011. However, at times we will use our interviews in ways more familiar to sociologists, to access the cultural meanings and structural systems that adhere to transplant. The data we collect from our interviews will be oriented towards both kinds of analysis; and documentation and transcriptions of speech will be treated as texts that provide access to discourse and values as well as to the past.

Another way of looking at this element of AboutFace is as a form of public history. This is a less well-defined but rapidly developing field, most often associated with the ways in which the past is made available to non-specialist audiences. It can also be understood as the examination of how history is made and mobilised in public, by the public, in response to contemporary concerns. Face transplants are a potentially fascinating case study of this form of history-making. AboutFace promises to offer insight into the ways in which the past is made and remade to answer questions about what is happening now. This is where the late twentieth century history of reconstructive surgery is critical, as an avenue to understanding how public perceptions of the face have been shaped (and reshaped) by cultural and social changes. The project sees face transplants as an access point to far-reaching social questions about facial difference, body image and appearance, which are particularly acute in the age of social media and the selfie. This means that we’re interested in popular perspectives, and in how recipients and others have presented themselves, and been presented, in the media, online and in fiction.

The ongoing challenge of categorising AboutFace as history is one of the many things that makes the project attractive to me as a historian. I feel that such uncertainty, although methodologically and theoretically destabilizing, is also productive. It forces us to push to the edges of our disciplines and knit them together with other fields in ways that feel truly interdisciplinary. I will continue to reflect on this as the project develops and report here regularly on our responses to methodological and disciplinary challenges as they emerge.